Day 5 – Giants’ Causeway and the Dark Hedges

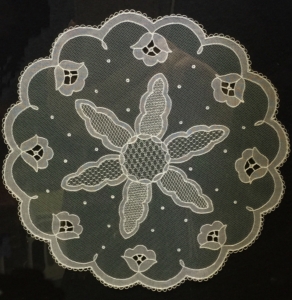

Seascapes series © Breda McNelis, fiber artist https://bredamcnelis.ie/

As a member of one of my favorite organizations, the Contemporary Quilt Art Association, I’m hoping to enter an exhibition next year called “Natural Geometry”. Boy, do I have inspiration to tackle that theme! A World Heritage site, the Giant’s Causeway is comprised of polygonal basalt blocks, most frequently 6-sided but some have 4, 5, 7, or 10 sides.

Basalt rock formations at the Giant’s Causeway, Northern Ireland

The legend behind the name of this geological wonder goes as follows. The giant from Ireland, Fionn mac Cumhaill (aka Finn McCool) is being threatened by the Scottish giant Benandonner across the sea. Finn grabs up huge rock pieces from the coastline and throws them into the sea, to make a pathway for Finn to go across. However, when he gets across, he realizes that Benandonner is terrifyingly massive! Finn rushes back home to Ireland where his wife disguises him as a baby. When the Scottish giant comes to their door and sees McCool as a baby, he thinks the father must be much larger than he is, so he races back across the rock bridge to Scotland, causing most of the bridge to sink!

The Giant’s steps

One of the things that surprised and delighted me was the gift shop and interpretative center. Rather than just have the typical tourist doodads, they had a wide variety of quality artwork from local artisans, fiber art included!

Giant’s Causeway © Breda McNelis

Breda McNelis is one of the textile artists that are represented by the shop. Her work is inspired by the colors and textures of the Irish landscape. She also works with traditional Irish fabrics- Báinín, a traditional Irish fabric which is an un-dyed, woven 100% natural wool and colorful Donegal tweeds. Her pieces are layered with silk fibers, hand-painted silks, merino wool, and beautiful yarns.

You can find more of her lovely work on her website at https://bredamcnelis.ie/

“Sunset, Giant’s Causeway” © Breda McNelis

Christina Fairley Erickson at the Giant’s Causeway

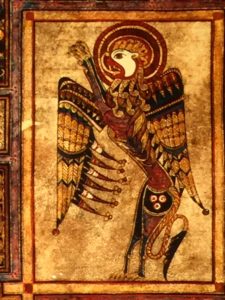

The mystery and magic of the Causeway Coastal area at the North-western edge of Ireland has drawn tourists for 400 years, but most recently has gained greater fame from the Game of Thrones series. With the abundance of medieval buildings, beautiful landscapes, and mysterious caves, Northern Ireland became a natural location for filming this fantasy mega-hit.

One of the locations, “The Dark Hedges”, was used as the Kingsroad for the people of Westeros and was shown in Season 2, Episode 1 when Arya Stark escaped King’s Landing in the back of a cart. Planted in the 18th century, the intertwining beech trees create a spooky, other-worldly setting.

In 2016, storm Gertrude hit Northern Ireland with 130 km/hr winds, causing a number of the trees to fall. But the creative genius of the people of this area took this tragedy and made something beautiful out of it. The huge trunks were removed and a group of designers and craftsmen interpreted different scenes from the Game of Thrones Session 6 into a series of 10 incredibly carved doors. Each of the doors were then installed at a pub at a Game of Thrones film location in Northern Ireland. Click here to see a short film on the making of the Doors of Thrones.

Coming soon: Blog on the “Game of Thrones Tapestry”!

The Dark Hedges aka the Kings Road in the Game of Thrones

The soaring and mysterious Dark Hedges

Towering columns of the Giant’s Causeway

The Giant’s Causeway steps into the Inner Sea between Northern Ireland and Scotland

One of many wooded lanes lending to the mystical atmosphere in Northern Ireland

As many of you know, I have a wee bit ‘o Irish in my heritage. My paternal great-grandfather, Robert Fairley, emigrated from Lisburn in Northern Ireland around the turn of the century. I also have two g-g-grandparents from Ireland from different sides of my family tree. So between my familial name, red-headed genes from my Dad, and family lore, being Irish was the strongest ethnic identity stressed in my childhood.

As many of you know, I have a wee bit ‘o Irish in my heritage. My paternal great-grandfather, Robert Fairley, emigrated from Lisburn in Northern Ireland around the turn of the century. I also have two g-g-grandparents from Ireland from different sides of my family tree. So between my familial name, red-headed genes from my Dad, and family lore, being Irish was the strongest ethnic identity stressed in my childhood.

Some of the height of the collection includes pieces made for Queen Victoria, including a Golden Jubilee damask table doily from 1887 which was part of a set of 24 damask doilies depicting the new Royal Irish Linen Warehouse and a set of different miniature household items made for Queen Mary’s dollhouse! There was also information about Irish designer Sybil Connolly (1921-1998), who took inspiration from traditional Irish clothes and fabrics. Her clients included the Rockefellers, Mellons, Elizabeth Taylor, and Jacqueline Kennedy.

Some of the height of the collection includes pieces made for Queen Victoria, including a Golden Jubilee damask table doily from 1887 which was part of a set of 24 damask doilies depicting the new Royal Irish Linen Warehouse and a set of different miniature household items made for Queen Mary’s dollhouse! There was also information about Irish designer Sybil Connolly (1921-1998), who took inspiration from traditional Irish clothes and fabrics. Her clients included the Rockefellers, Mellons, Elizabeth Taylor, and Jacqueline Kennedy.